Updated June 9, 2022

Most people hit their peak earning years in their 50s and 60s. Consequently, these also tend to be the peak tax years. On the face of it, converting an IRA to a Roth IRA doesn’t look like an obvious choice. The act accelerates deferred income into the current year and stacks on top of everything else you’ve already made. Conversions increase your current year tax bill.

The emphasis is on “current year”. There are situations where Roth IRA conversions can lower total taxes paid over your lifetime. Moreover, with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 your beneficiaries can walk away with some unique tax-free compounding opportunities following your death when you complete Roth conversions (or just generally find a way to sock money into a Roth over your lifetime).

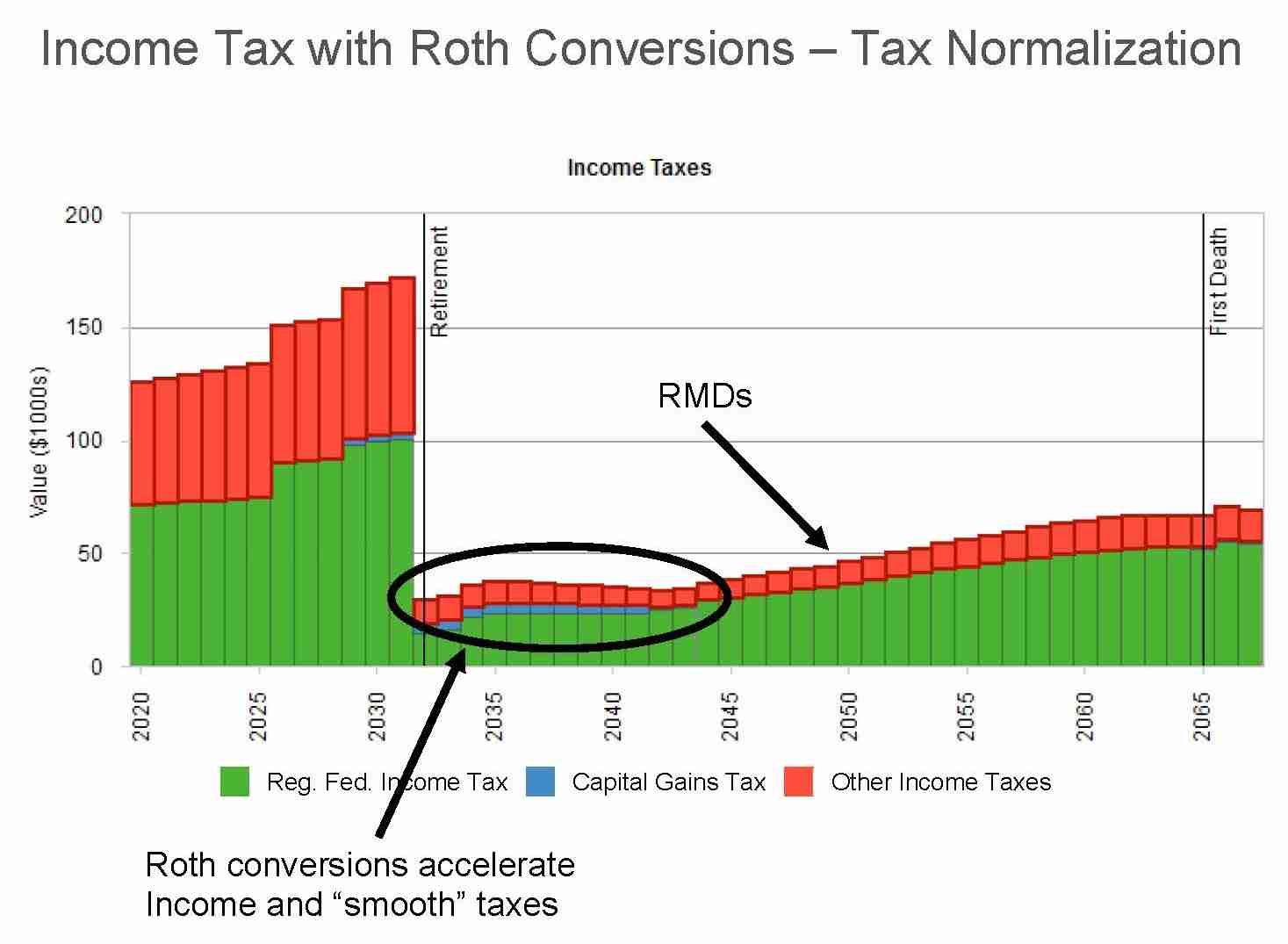

The prevailing school of thought around Roth IRA conversions is that they should be performed only when current tax rates are expected to be lower than future tax rates. That’s a good practice but it’s only half of the battle. Roth IRA conversions can also be used to smooth and in some cases reduce future taxes by accelerating what would otherwise be deferred income to the current year. Of course your income sources, tax bracket, retirement date, and portfolio composition all play a role, but when these factors coalesce in the right way a conversion to a Roth IRA can become a powerful tool.

Tax normalization

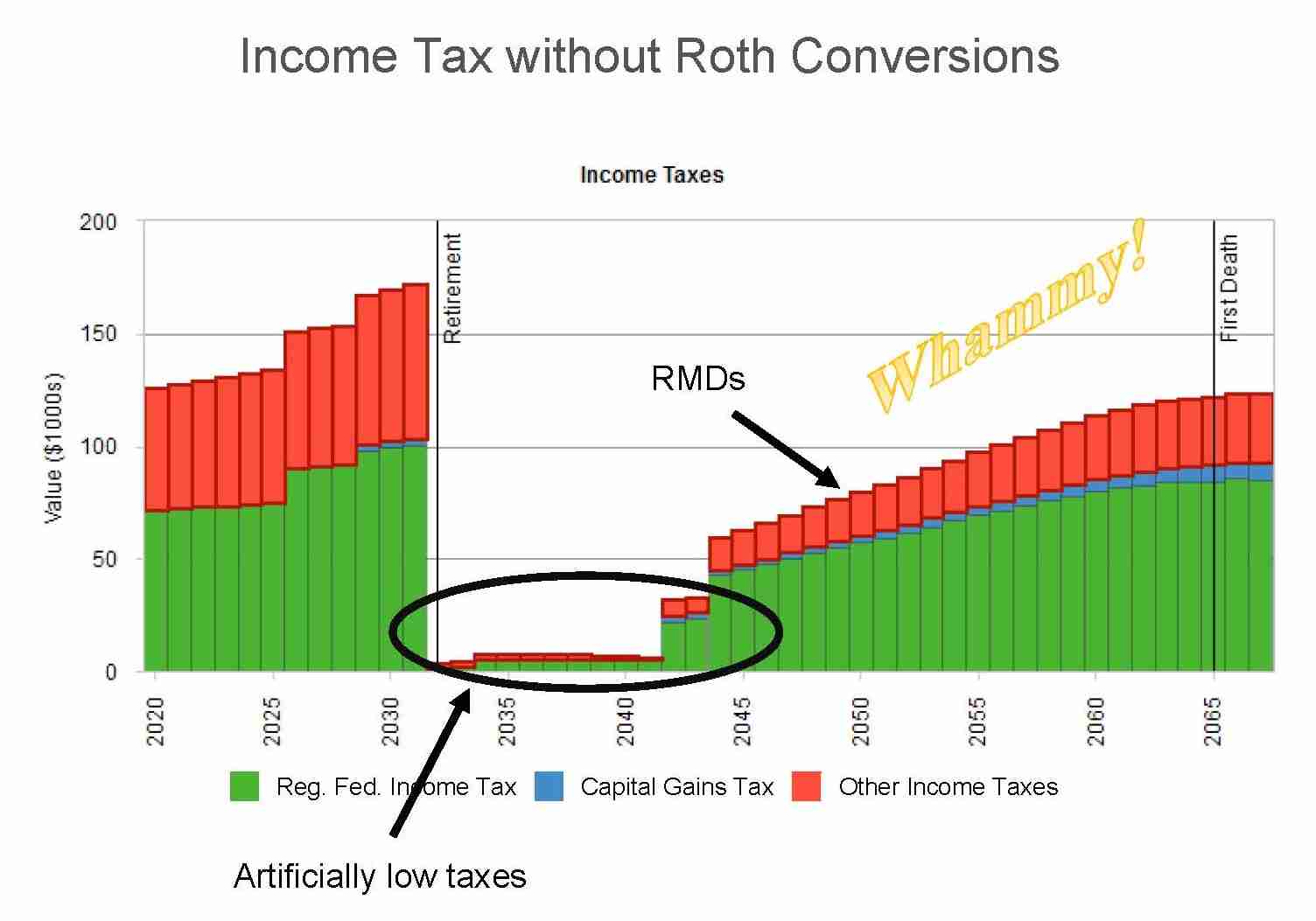

EAs and CPAs can rejoice at this. Tax normalization is the idea of accelerating income into the years between your retirement date and your required beginning date for Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) to ‘smooth’ and moderate your tax bill over time. It works like this – say you retire at age 65 with social security, a small pension, your 401(k), and a taxable brokerage account that you plan to use to fund your lifestyle for the rest of your days. Odds are you’ll want to tap your 401(k) for income last.

The general pecking order for distributions is to take from taxable accounts, then tax-deferred accounts, and finally from tax-free accounts. It’s usually a good idea to hold off on withdrawals from anything that will compound tax-deferred or tax-free. But, doing so can leave you in a tough spot when you pay almost nothing in taxes in the first few years of retirement followed by hefty taxes when you hit RMDs. The extra years of compounding will increase your retirement plan balance, which increases your RMDs and can potentially bump you into the next bracket.

This is because anything you take from your 401(k), or any other tax-deferred retirement account, will count as ordinary income for the year. This Is the same classification as the wages you received from your job before you retired. Taking $40,000 from your 401(k) is no different tax-wise than if you made $40,000 as a company employee.

Compare this to your taxable brokerage account, which would mostly be capital gains. (This isn’t a hard and fast rule and you can get hit with tax from some strange angles in a brokerage account depending on what you hold). Capital gains tax rates are currently lower than ordinary income tax rates. Money spent from this account would generally create less tax than your 401(k) in the current year.

The rare case when tax deferral works against you

Every year you don’t take money out of the 401(k) is another year that its balance grows larger. (We’re giving you and your investment prowess the benefit of the doubt here and pretending that recessions don’t exist, though will get more into that later). You could continue to defer withdrawals until age 72 when required minimum distributions (RMDs) begin.

Let’s say that’s exactly what you did. You deferred taking money from your 401(k) from age 65 to 72 and let the account really balloon upwards. When you do hit age 72 your RMD is likely to be big. Really big. You will need to take out a little shy of $40,000 for every $1,000,000 you have saved in tax-deferred retirement accounts for your first RMD. (Schwab has an easy to use calculator to help estimate this).

This is a non-negotiable withdrawal as well. You must take the money out even if you don’t need it. The money you take out will create a noticeable tax hit. In a worst-case scenario it may even bump you into the next tax bracket

This is where “normalizing” your taxes over those seven years starts to look attractive. You do this by accelerating income into each of those low tax years via converting an IRA to a Roth IRA. The goal is to do just enough so that your taxes end up being roughly what they were while you were working.

This has a few advantages. Roth IRAs grow tax free. You’re gaining a powerful compounding tool. Your RMD at age 72 will be less than it otherwise would be had you elected to defer withdrawals instead of convert. This, too, will help bring down your taxable income when you hit age 72. Perhaps best of all, Roth IRAs do not have a required minimum distribution. Money that goes into a Roth can stay in a Roth until the day you die. Even then, your beneficiaries could get up to another 10 years of tax-free compounding in the Roth IRA following your passing.

When your children finally say thank you

The SECURE act made significant changes to inherited IRA distributions. Spouses can still “stretch” distributions over their lifetime or roll your old accounts into theirs. But kids and grandkids who inherit a Roth IRA are subject to a new 10-year rule. They can take everything on day one, 1/10th a year for ten years, or take everything on the last day of year ten. It doesn’t matter when in that period it goes so long as the account is drained at the end of year ten.

If you have children or family members to whom you’d like to leave assets, converting an IRA to a Roth IRA can be especially compelling. You effectively add an extra ten years of tax-free growth to whatever your lifespan was. This is enough time for the account to double if it averages a reasonable 7.2%/year growth rate over that decade. If you’re in a 20% effective bracket, you could perform a single conversion for $50,000 at age 65. Your tax would be $10k on the transaction. Say it doubles twice before you pass away at age 85 and then doubles again over the next ten years that your beneficiaries have it. For a one-time $10k payment you are able to parlay $400,000 tax-free to your beneficiaries. Where else does that deal exist?

This stands in contrast to an inherited traditional IRA, which is 100% taxable to the recipient and is subject to both required minimum distributions and the new ten-year rule. We wrote a detailed primer on this last year. This compressed distribution schedule could be a complicating factor, particularly if your child is a high wage earner or married to a high wage earner (even better!) But those factors aren’t there with a Roth IRA – it’s tax free. Your beneficiary won’t owe a penny. They can let the account compound tax-free for another decade following your passing. This is a big deal.

However, no strategy is completely without its drawbacks.

There is no “CTRL+Z” undo magic

Up until 2018, if you converted an IRA to a Roth IRA you could undo it through a process called recharacterization. This worked well if you got cold feet, had a big change in income for the year, or more commonly saw significant declines in your portfolio due to a bad market.

Many people choose to withhold tax from the amount they convert to help mitigate the tax impact. This is rarely a good idea. Fewer dollars trickle into the tax-free account and if you’re under age 59.5, the withheld taxes are considered an early distribution subject to the 10% penalty! Nonetheless this still remains a popular choice.

If you converted $50,000 and withheld 15% for taxes, the net amount deposited to the Roth IRA would be $42,500. If the market then declined by another 15%, your Roth IRA would dip to $36,125. That’s a tough pill to swallow. Had you done this prior to 2018 you’d be able to undo it and recoup the portion lost to taxes.

This may not seem like much but consider how much extra you would have to earn on the ~$36,000 to get back to where you started. You need a little over 38% to get ~36,000 up to $50,000. You only need 17% to take $42,500 back up to $50,000. That’s a big delta. And now its one you can’t undo.

How you pay tax matters

Paying tax from an outside account when converting an IRA to a Roth IRA works best. You are maximizing the amount of money held in a tax-free environment and reducing money held in a taxable environment. Pretty straight forward. Paying the tax from the amount converted can still be a good strategy, but only if you’re converting at a lower rate than what you would have paid down the road when taking funds out at for your RMD. Even then it still isn’t ideal.

There is a potential tax trap in all of this. You need to think twice if you plan to pull money from the Roth IRA shortly after conversion.

The five-year rules

Roth IRAs have a unique rule not applicable to any other type of retirement account. After converting your IRA to a Roth IRA, you must wait five years before withdrawing any portion of that specific conversion. This is because each individual conversion you perform has its own five-year holding period before the converted amounts can be withdrawn penalty free (Treasury Regulation 1.408A-6, Q&A-5(b)). But, this rule only applies if you are under age 59.5.

Roth IRAs allow you to withdraw principal tax and penalty free at any time. This 5-year rule was put in place to keep people from doing a Roth conversion and immediately withdrawing funds as a way to skirt early distribution penalties on a traditional IRA. But, there are no early distribution penalties once you hit 59.5 and therefore no holding period requirement when you reach that age!

But to make it extra tricky, there is a second five year rule that applies to the growth on your Roth contributions (converted principal included). Essentially, the Roth must be open for at least five years before any of the growth on your contributions is tax-free.

Seeing it in action

Say you convert $20,000 from your IRA to your Roth IRA at age 55. Three years pass and the balance grows to $24,000. You decide to completely withdraw and drain the account. The full $24,000 is subject to the 10% early distribution penalty as the account hasn’t been open for the requisite five years and you aren’t yet 59.5. The $4,000 of earnings is also subject to taxation at ordinary income rates on top of penalties despite being in a Roth IRA (rule #2). It’s a double whammy.

That’s all kinds of bad. The only silver lining to the above is that distributions from your Roth are made on a first-in, first-out basis. This means that the converted principal is the first chunk of money to leave the account. If you had distributed $20,000 or less, you would have incurred only the penalty. The $4,000 of earnings would still remain in the Roth growing tax and penalty free.

Tax years vs. calendar years

There’s one more wrinkle to all of this. The five-year time clock is measured by tax year. This stands in contrast to contributions, which can made as late as the tax filing deadline of the following year for an effective date in the current year. It sounds more confusing than it is.

You can make a contribution as late as April 15th of 2023 that will count for the 2022 tax year. If you complete a conversion in February of 2023, it will only count in that calendar year. You cannot backdate conversions to previous tax years like you can with contributions. If you want that Roth IRA conversion to count in 2022, then you need to get it done by December 31st, 2022. The differences between conversions and contributions are admittedly nuanced but it’s important to get it right to avoid a surprise when you file your taxes!

However, this isn’t all. When you convert your IRA to a Roth IRA, the transaction is backdated to Jan 1st of the current year regardless of when in the year it actually occurs. This goes for all conversions in the current year. For tax purposes they will be lumped together and considered to be a single Roth IRA conversion regardless of how many conversions you perform throughout the year.

Functionally this turns your five-year holding period into four years and a day. If you complete a conversion on December 31st, 2022 it will be backdated to January 1st, 2022. Add five years and the clock expires on January 1st, 2027. Counting the actual number of days elapsed from 12/31/2022 to 1/1/2027 and you get four years and day. Pretty cool!

Of course, none of this matters if you don’t intend to draw from the Roth or at least draw from it anytime soon. However, if you’re working in Roth distributions to your income strategy then you need to keep track of your conversion dates. Confusing your Roth IRA with your Roth 401(k) also matters.

All this tends to track fairly easily when you only have a Roth IRA to focus on. Adding a designated Roth account in a 401(k) to the mix can open some fantastic planning opportunities but does muddy the water.

Roth 401(k) balances and in-plan conversions

The Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 created the opportunity for what we now call an intra-plan Roth conversion. Its exactly what it sounds like. You can convert a pre-tax balance in your 401(k) to a designated Roth account in your 401(k).

This works nearly identically to converting an IRA to a Roth IRA. You must pay tax at ordinary income rates on whatever you convert in the year that you complete the conversion. The five-year holding period rule also applies to each separate conversion you make to a designated Roth account in your 401(k) if you’re not yet 59.5. Moreover, each employer plan has its own five-year holding period requirement!

The holding period requirement can’t be aggregated across employer plans, either. If you have converted and satisfied the five-year holding period in plan A, you cannot apply that length of time to the conversion you only just performed in plan B. However, there is a workaround for contributions.

If you rollover contributed amounts from plan B to plan A above, then the holding period for whichever plan has been around longer prevails! Consider this example:

- You have a $100,000 total balance in your current employer’s 401(k), of which $80,000 is pre-tax contributions and $20,000 is Roth account contributions. The Roth contribution account is three years old. You have another 401(k) plan at a previous employer with a total balance of $250,000, of which $50,000 is in a designated Roth account that has been open for 8 years. If you were to withdraw the Roth portion of your current employer’s 401k, you would run afoul of the five-year holding period rule and face penalties and taxes. However, if you rolled those Roth account contributions to the old employer’s 401(k) that has been open for eight years before making the withdrawal, then you would be fine!

The example above only works for contributions since each Roth conversion from a designated Roth account in a 401(k) has its own five-year holding period rule. You can’t aggregate time across plans on conversions in the same way that you can for contributions. It’s a small but critical detail.

Moreover, the five-year holding requirement doesn’t carryover when you roll your Roth 401(k) to your Roth IRA. If the Roth 401(k) has been open six years and the Roth IRA for just one when you roll funds over, the six years on the Roth 401(k) will be lost. You’ll be subject to the Roth IRA holding period and will have another four years to go!

This is a critical detail when it comes to Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Roth IRAs are not subject to RMDs but a Roth 401(k) is. To avoid forced liquidation of tax-free money it usually makes sense to roll the Roth 401(k) into a Roth IRA, although this could put the Roth 401(k) under a new five-year clock. It usually makes sense to open a Roth IRA well before age 72 just to get the five-year clock started, even if you only put a nominal $100 in the Roth IRA.

So how do you distinguish what was converted vs. what was contributed? The short answer is that you don’t – this responsibility lies with the plan administrator. Not all of them track these details, either. This means that even though you have the ability convert, rollover, contribute, etc., if you aren’t in a plan that distinguishes between these then the planning opportunity is lost to you. This becomes an even bigger issue when converting after-tax money in a pre-tax account to a Roth IRA or designated Roth account in a 401(k).

Converting after-tax IRA money

Contributing after-tax money to a pre-tax account, such as an IRA or a 401(k), is an ubiquitous planning strategy. No tax deduction is given on any money contributed but all growth on that contribution accrues tax deferred. It adds some complexity to your taxes each year but can yield results over the long-term.

Converting the after-tax money in your pre-tax account to a Roth IRA can be a smart move in certain situations. (This is commonly called a “backdoor Roth IRA”). After all, if you don’t get the deduction you may as well get the tax-free growth! However, the pro-rata rule can limit the efficacy of this strategy if you have a large IRA balance.

The pro-rata rule

The rule states that any sum converted from a pre-tax, Traditional IRA is converted pro-rata between pre-tax and post-tax contributions – you don’t have the option to pick and choose which contributions are converted. Take the following example:

- You have a Traditional IRA totaling $500,000, of which $100,000 is after-tax contributions (i.e. 20% of the account value). If you were to convert $100,000, you would not get to select or designate the portion you are converting. Instead, the IRS views the transaction as though 20% of the $100,000 is after-tax money and 80% is pre-tax. Your taxes would show an extra $80,000 in income for the year based on the pro-rata conversion rule.

Moreover, all IRAs are lumped together when considering the pro rata rule. Continuing from the example above, let’s say that the $500k was spread across three different IRAs. IRA number 3 contains $100,000 of after-tax money. Even if you converted just this account you would still be subject to the pro-rata rules! $80,000 of the conversion would be included in your gross income for the year regardless of the fact that you converted from an account that contained only after-tax money.

This can be confounding. The IRS aggregates all of your IRAs together when applying the pro-rata rule (this is known as the IRA aggregation rule). To them, keeping all your after-tax money in one account doesn’t make a difference. They’re still going to look at the conversion as if you had consolidated all of your IRAs before completing the conversion. Holding after-tax contributions in a separate IRA may help for your mental accounting, but it will do nothing for your conversion strategy or tax planning.

A simple fix to dodge the pro rata rule

However, the workaround for this is a simple one. Roll your pre-tax IRAs into a workplace retirement plan (you must have a plan willing to accept the rollover for this to work!) This will isolate the after-tax IRA in the example above allowing you to convert the full value without running afoul of the aggregation rule or the pro-rata rule. Easy!

But what happens if the IRA you want to convert has both pre-tax and after-tax funds sitting inside it? The rollover to a qualified plan still works! The rules under IRC Section 408(d)(3)(A)(ii) states that the pro-rata rules do not apply and the pre-tax funds are rolled over first when a rollover occurs from an IRA to a qualified plan. The IRS treats it as though only pre-tax money was moved when you do this transaction.

Converting after-tax 401(k) money to a Roth IRA

The rules for converting funds from within a 401(k), 403(b), or 457(b) are more involved, which give you the opportunity for some great tax plays but only if you’re careful! For starters, current regulations allow for after-tax contributions to employer sponsored retirement plans but only some of them actually offer that feature. Its entirely up to your employer as to whether you can contribute after-tax money.

Assuming it’s allowed in your plan, you can contribute after-tax sums above and beyond the elective deferral limit ($27,000 in 2020 with the over 50 catch up contribution) all the way up to the annual additions limit ($61,00 in 2022). This is up to $34,000 of possible after-tax money in your workplace retirement plan. An employer match or profit-sharing contribution also goes towards the $61,000 total and would reduce the amount of after-tax money you can throw in.

Full direct rollovers – easy and straightforward

If you do decide to convert from a 401(k), the IRS allows you to separate the after-tax funds from the pre-tax funds at the time of conversion, but only as part of a full direct rollover (i.e. the money goes directly from institution A to institution B). The caveat is that you, as the plan participant, must notify your employer of your intention to split the rollover between a traditional IRA and a Roth IRA. This is a far cry from converting an IRA to a Roth IRA in which there is no pick and choose.

So, if you have a $100,000 total balance of which $20,000 is after-tax contributions, then you would need to notify the plan administrator that you should be receiving two checks: one for a traditional IRA and one for a Roth IRA. Absent these instructions, the plan admin would ostensibly cut one check for a $100,000 that would rollover both the pre-tax and after-tax contributions to a single IRA. (You should only receive one 1099-R at the end of the year to report this transaction as it’s considered one transaction with two checks. Nevertheless, many plan admins send two 1099-Rs, one for each distribution, even though its considered a single disbursement.)

Partial rollovers – messy

Its worth noting that the pro rata rule does apply if you complete a partial rollover and conversion. Carry forward the example from above where you have a $100,000 balance and $20,000 (20%) of it is in after-tax contributions. If you withdraw just $20,000 of it, the pro-rata rule will apply in determining what is after-tax and what is pre-tax.

So, $16,000 would be pre-tax (80%) and $4,000 would be after-tax (20%). You still retain the ability to dictate that the $4,000 in this example be part of a Roth conversion – that aspect doesn’t change. But you don’t get to select which segment of the 401(k) money you are converting when you perform a partial conversion.

We’ve seen these rules trip up plan administrators. The current rules came over several iterations of earlier rules, and some admins haven’t quite kept up with all of the changes. You may be given the opportunity to designate which portion of your 401(k) you are using for a partial rollover, but this is wrong and won’t hold up under audit. If completing a partial rollover, ensure that your plan admin correctly issues your 1099-R reflective of the pro-rata rule for partial rollovers!

Arcane rules on intra-plan conversions

There are a few more wrinkles in this. First, all conversions from a workplace plan are considered distributions. As distributions, they are still subject to the pro-rata rule discussed ad nauseum above. Moreover, if you withhold tax from the converted amount and are not yet 59.5 years old, then the taxes withheld will be counted as an early distribution subject to the 10% penalty just as they would be for a Roth IRA.

What’s unique about conversions within a plan and not out to a Roth IRA, is that the IRA aggregation rules do not apply. This means that if you have three 401(k)s totaling $500,000 and 401(k) number three has $100,000 of all after tax money, you could convert just 401(k) number three and effectively complete a tax-free Roth Conversion. Why? Because you can disregard the other $400,000 held in those other pre-tax 401(k)s when completing this conversion! Aggregation rules hold no sway here. It works the same way for a 403(b) or a 457(b).

Remember though, for this to be possible your plan must allow for designated Roth accounts, after-tax contributions, and in-plan conversions. While these features are becoming more and more common we still see quite a few plans out there that don’t offer all of these. Or more strangely, offer just some of these or offer them with restrictions.

Indirect rollovers – confusing and tricky

There’s another old rule that does allow for just the after-tax portion to be taken out first, but for this to work it can’t be part of a direct rollover or conversion and your plan admin must keep a separate accounting for the after-tax contribution and its associated growth. This means the funds must land in a checking/savings/investment account and not your Traditional or Roth IRAs. However, you can move these sums into Roth and Traditional IRAs as part of an indirect rollover after they hit your checking account if done within 60 days of the initial distribution.

If this is done, you have the ability to move just the after-tax contribution and it’s associated growth while applying the pro-rata rule solely to these two components, thereby ignoring the other pre-tax sums in your account! It’s easier to understand if you see it in action:

- Assume you have a $100,000 401(k) account balance with $40,000 of after-tax contributions and $10,000 of associated growth on those contributions. With your plan admin keeping a separate accounting of these, you can distribute, not rollover $40,000 from the after-tax share and have it treated as 80% after-tax ($40,000 of the $50,000). You’ll get $32,000 of after-tax money you can subsequently move to a Roth IRA and $8,000 of pre-tax that can move to a Traditional IRA.

There’s just one little hiccup to the example above. When you distribute money from a 401(k) that is not part of a direct rollover, regulations mandate 20% federal withholding on any taxable amount distributed. This means that of the $8,000 pre-tax portion paid to you in the example above, you’d only receive $6,400 after withholding. You’d need to come up with another $1,600 to roll the full $8,000 into an IRA. Making matters worse, if you’re under age 59.5 when you complete this transaction you’ll be subject to a further 10% penalty on the $1,600 deemed to be a distribution.

Despite this, the rule and the separate accounting does allow you to convert more of the after-tax share. You move $32,000 of after-tax money in the previous example. Absent this you would only be able to move $16,000 of the after-tax share when the pro-rata rule is applied to the full account balance.

Real life planning strategies for converting an IRA to a Roth IRA

Let’s work with some constraints to see how the rules we’ve been discussing actually play out in the real world. Pretend that your employer allows you to make after tax contributions, has a designated Roth account, and allows for in plan conversions at any time but only on after-tax sums contributed.

If you maxed out your pre-tax elective deferrals and then contributed after-tax sums on top of it, you’ll be limited to partial conversions only. Your employer won’t let you roll over the elective deferrals. The pro-rata rule will therefore apply and the after-tax sum you convert won’t truly be a full conversion. For example:

- You have $100,000 total balance of which $20,000 is after-tax contributions. Following your employer’s rules, you elect a partial intra-plan conversion for the $20,000 of after-tax money. Only 20% of the amount converted will actually be considered after-tax ($4,000). Your account has a bit of a strange composition following the conversion with $20,000 in a designated Roth account, $16,000 of after-tax money, and $64,000 of pre-tax money.

Even though you converted an amount equivalent to the after-tax sum in your 401(k), the application of the pro-rata rule due to the partial conversion means that you still retain a considerable portion of the after-tax dollars in your 401(k)!

The better option here would be to avoid an in-plan conversion entirely and elect for a full distribution and direct rollover, assuming the plan allows for it (it doesn’t in our example). A full distribution avoids the pro-rata rule and allows you to elect what goes where, thereby providing the opportunity to fully convert the after-tax money and roll the pre-tax amount to a Traditional IRA. In practice however, the plan administrator may not allow you to roll out your entire balance if you’re still working for the company. Some may not allow in-service distributions at all.

Alternatively, you could simply contribute to the designated Roth account for your elective deferrals and then max out with after-tax dollars. This cuts down on the pre-tax dollars in the plan considerably but doesn’t avoid them entirely. Any employer match or profit-sharing contributions received will be pre-tax. Additionally, all the earnings on your after-tax contributions will be pre-tax. Odds are your employer won’t let you convert your after-tax amounts immediately after every single contribution or will at least restrict the number of intra-plan conversions you can perform in a calendar year. It would severely limit the amount of pre-tax appreciation you earn on those contributions if you could, but even if it was allowed the administrative hassle on your part arguably isn’t worth it. 401(k) plan paperwork and coordinating with HR can be painful.

When Roth IRA conversions can hurt you

Despite the numerous benefits of tax-free compound growth afforded through Roth accounts, there are still certain situations where conversions can hurt more than they help. The most obvious, and also easiest to avoid, is completing conversions at higher tax brackets than you would otherwise recognize when withdrawing from pre-tax accounts in retirement. This ups your tax bill to levels it shouldn’t reach.

Simple online calculators can help you estimate this, but these are typically built around Federal income taxes. You’ll face tax from numerous sources in retirement and not all of the brackets neatly align with the Federal brackets. Your Medicare Part B and part D premiums are means tested and don’t match up with the Federal brackets. Big income years can skew you into a higher premium without necessarily bumping you into the next federal income tax bracket.

Additionally, Roth Conversions can eliminate the special Net Unrealized Appreciation (NUA) treatment you receive on employer stock when held in a pre-tax workplace retirement plan. Admittedly, this will only be an option for those who 1) have employer stock in their plan and 2) have owned it long enough or are lucky enough to have considerable appreciation on that stock. Regardless, Roth conversions will kill NUA benefits, which could be significant.

Perhaps the biggest drawback is for those looking to retire early. Withdrawals from retirement accounts of any kind are typically subject to penalties if taken before age 59.5, though some exceptions do exist. The age 55 rule is a common workaround to this that allows retirees to withdraw funds from their most recent employer’s retirement plan in the year in which they turn 55 if they separate from service. Completing conversions and rolling money out to IRAs and Roth IRA will mean there’s no penalty-free money left to live on if you retire between 55 and 59.5!

This of course can be avoided by simply completing an intra-plan conversion, which would leave funds in the 401(k), but is only an option for those fortunate enough to have that ability in their workplace plan in the first place. Absent that, a conversion strategy amongst old workplace plans may also do the trick while still keeping you eligible for the age 55 exception.

Lost tax credits and unseen thresholds

Roth conversions increase your taxable income for the year, which can A) subject you to new taxes that only kick in at certain levels and B) phase you out of certain tax credits. These can create “tax cliffs”, where even small incremental increases in income have a dramatic effect on your marginal tax rate.

Lost credits

Credits and deductions are not the same. Credits are far more powerful. Deductions reduce your taxable income, but credits provide a dollar-for-dollar reduction to your actual taxes paid! Its easier to see it in action. Below we have two people, both of whom are single tax payers making 100,000 in 2022. The first has a $2,000 deduction for contributing to an IRA. The second has a $2,000 credit for the American Opportunity Tax Credit.

The person with the tax credit is clearly better off. Credits reduce taxes owed. Deductions reduce the amount of income that is used to arrive at the total tax paid. Roth conversions can cost you credits if you’re not careful. Here are a few of the common credits we see people miss out on when performing conversions:

- Lifetime learning credit, $80k – $90k single or $118k – $138k married filing jointly

- American opportunity credit, $80k – $90k single or double that if married filing jointly

- Child tax credit, $200k – $240k single or double that if married filing jointly

- Qualified adoption expense credit, $217k – $257k single and married filing jointly

Note that every single credit listed has a range. These credits are phased out as income rises as opposed to stopping completely once a threshold is hit. You can still claim partial credits if your Roth conversions don’t push you past the upper bound of the phaseout limit!

Other important thresholds

But credits aren’t the only thing that’s impacted when Roth conversions push your income higher. You can also lose the ability to take certain deductions or may even get hit with new taxes. Specifically,

- Net Investment Income Tax (3.8% tax), $200k single or $250k married filing jointly

- Coverdell ESA contributions, $95k – $110k single or double that if married filing jointly

- Roth IRA contributions, $125k – $140k single or $196k – $206k married filing jointly

- Student loan interest deduction, $70k – $85k single or double that if married filing jointly

- IRA contribution deductibility when covered by qualified plan, $68k – $78k single or $109k – $129k if married filing jointly

- Top capital gains tax bracket (20% tax), $459,750 single or $517,200 if married filing jointly

Some of these limits are easy to breach. Roth conversions tend to work best when done in years when taxes are low. This means that converting in the year in which you retire and may not be ideal. You’ll likely have several months, maybe even most of a year worth of income. The same goes for a year when you sell a large asset like a rental property (no home sale gain exclusion) or a business.

Roth conversions are a wonderful and powerful tool, but only when done at the opportune time!

Changing tax regimes and state taxes

Last but not least, your Roth conversion strategy can be used as a hedge against unknown future tax regimes. Many of the tax cuts afforded to individuals in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2018 are temporary. The bulk of them will sunset and expire in 2025, at which point tax rates will revert to the higher levels last seen during the Obama administration.

Moreover, future political administrations may elect to implement new taxes or entirely new tax regimes to further their policy goals. The possibility of less favorable tax structures in the future can never fully be discounted, which makes tax-free Roth accounts an attractive hedge.

We’ve focused almost exclusively on Federal income taxes in this article, but distributions from pre-tax retirement accounts are also subject to state taxes. This can become a powerful factor to consider if you intend to change states in retirement. Alaska, Florida, Texas, Nevada, South Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming do not currently levy an income tax. If you intend to move to one of these states in retirement it may be best to hold off on Roth conversions until you officially meet the residency requirements in your state of choice. The converse is true if moving out of one of those states; you may want to accelerate Roth conversions before you leave to avoid your new state’s income tax.

There aren’t any silver bullets or one size fits all strategies when it comes to Roth IRA conversions. These have to be done on a case by case basis. The bottom line is this: when done correctly a conversion can be a powerful tool to decrease total taxes paid over your lifetime and maximize what you’re able to leave to beneficiaries.