The Federal Reserve is raising interest rates this year with several more hikes expected before year end. This will be the first time in almost three years that the Fed has raised rates and tightened fiscal policy. The pivot to a hawkish stance is expected – inflation is running hotter than at any point in the last forty years. So what exactly is going to change?

Increase in the Federal Funds Rate

The Federal Funds Rate is the average rate that banks pay for overnight lending in the Federal Funds Market. Banks make loans and take in deposits every single day, but these values rarely ever match up precisely. If a bank loans out more than it takes in and dips below its reserve requirement, then it’s got to borrow from another bank overnight to plug the shortfall. This overnight lending is the bedrock of the financial system. Liquidity dries up and banks cease to function properly without it.

This overnight rate is about as low as you can get. The Federal Reserve doesn’t mandate a specific rate that banks charge one another to do this, but it does use various tools to help target a specific rate in the Federal Funds market. When the Fed wants to slow down an economy, it uses those tools to target a higher rate in the Federal Funds Market.

The higher targeted rates make it more expensive for banks to lend to one another, and the more expensive it gets the less likely the banks are to do it. This has a few implications.

Less liquidity in the system

Raising the Federal Funds rate makes it more expensive for banks to do business. They’ve got to maintain a positive net interest margin (i.e. payout less than they take in), which means that when their baseline overnight rises, all other interest rates have to rise with it. This means costlier car loans and mortgages, among other things. Higher rates mean consumers are less likely to take loans. Higher rates also mean that banks must become more selective about who they loan to – the cost of a default on a 6% loan is 3x more costly than a 2% loan. Those loans that could have been made sit on the bank’s balance sheet as deposits instead. This sucks liquidity out of the system and slows down the economy.

The increased Fed Funds rate trickles through banks to businesses who, just like consumers, are less likely to seek out loans. Higher financing costs means reduced spending and capital expenditures. New projects and developments that may have been slated when financing costs were lower get scrapped. Infrastructure isn’t built and jobs aren’t created. General economic development slows down, too.

Increased savings

Additionally, saving money gets more attractive just as loaning it out becomes less attractive when the Fed Funds rate rises. Savings accounts pay more interest. This attracts greater deposits as consumers have an increased incentive not to spend.

Businesses, who may have drawn down credit lines and hoarded cash when money was cheap, will pay it back. Money that might have gone to a speculative project because there was nowhere else to put it may be saved instead. Businesses have an incentive not to spend, too.

Stronger Dollar and Fewer Exports

US investors aren’t the only ones tempted to save when the Fed Funds rate increases. Foreign governments and investors are also tempted to shift money into US dollar denominated products as interest rates rise. But to do this the foreign investors must first sell out of their existing investments in their local currency. This reduces the demand (and value) of the local currency relative to the dollar, which in effect increases the value of the dollar.

Interest rates aren’t the only factor impacting the dollar’s value, but it does tend to lead to a stronger dollar in most cases. The stronger dollar, in turn, reduces demand for US goods abroad as the exchange rate becomes less favorable. US exports decrease. Manufacturing and other sectors of the economy slow down as demand declines.

The stronger dollar is great for savers, but it also tends to drag down the speed of growth in an economy over time.

Increased Prime Rate and Financing Costs

The increase in the Fed Funds rate effectively means higher financing costs for everyone in the US. Banks must maintain their net interest margin mentioned earlier, which means that as their financing costs increase so must that of their customers. Banks raise the Prime Rate, which is the best and lowest rate that banks rollout for their most credit-worthy customers.

The prime rate impacts everything from credit card rates and personal loans to variable rate mortgages and home equity loans. As financing costs increase, consumers are incentivized to save instead of spend. Those with variable rate mortgages are in a particularly unique position when the prime rate rises. They don’t have a choice but to spend more as their mortgage rises, which reduces their disposable income and drives down consumption.

Headwinds for Stocks, Bonds, and Housing

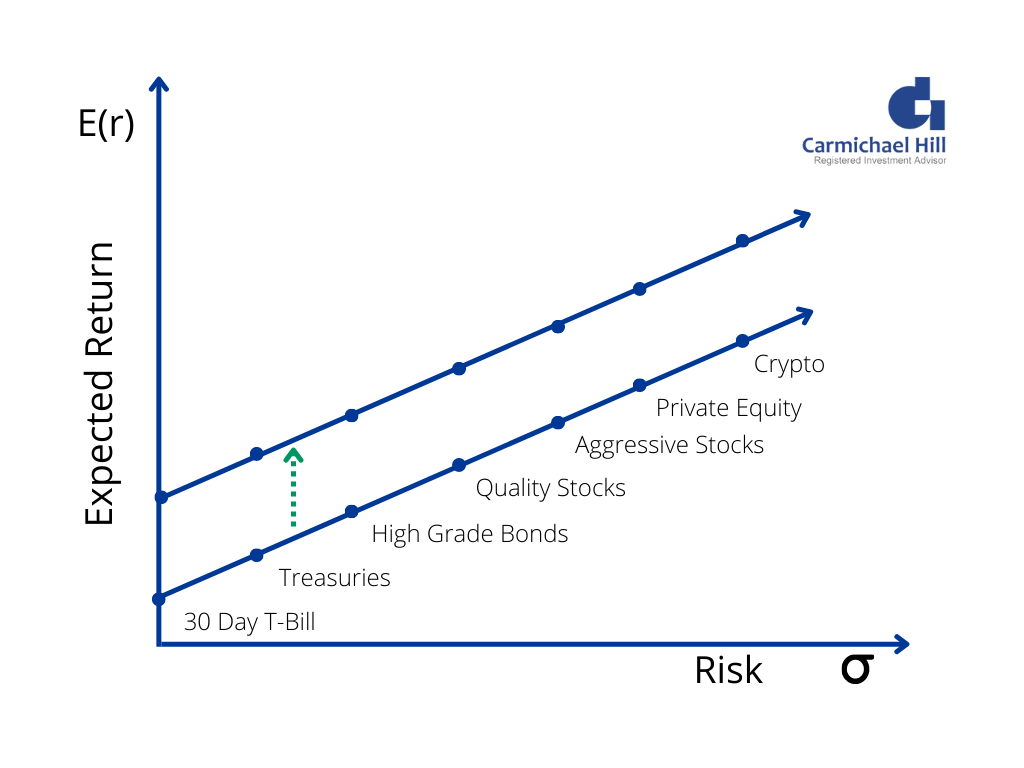

Raising the Fed Funds rate, and in turn all other US interest rates, impacts the stock and bond markets, too. It increases the Risk-Free Rate of Return. This is the rate someone can expect to earn while taking zero risk. The 30-day T Bill is generally considered to be the best proxy for this rate, since the government can print all the money it needs to avoid going broke by the end of the month and 30 days is too short a time frame to lose purchasing power to inflation.

When this rate rises, so must all other rates. After all, who will invest in a risky asset that pays less than the risk-free asset?

This is seen easily on the Capital Markets Line below. A shift up in the risk free rate moves everything else up with it. All assets must suddenly pay more! But they can’t. There isn’t a secret money tap that can be turned on to generate overnight profit. Instead, assets reprice downward in order to generate the new “earnings yield” that keeps them competitive with the risk free rate.

Bond prices drop, yields rise, and credit dries up

Bond prices and interest rates are inversely correlated. As one goes up the other must go down. It’s pretty intuitive – if you have a bond paying the market rate of 5% and rates rise to 6%, then your bond is now less attractive when compared to all of the new bonds that come to market at the higher rate. Nobody is going to pay $1,000 for your bond at 5% when they can get a new bond paying 6% for that same $1,000.

But, when bond prices dip their yield goes up! That 5% bond mentioned earlier pays $50/year in interest (i.e. 5% of its original $1,000 price). If it reprices down to $833 when interest rates rise, then its yield changes to $50 / $833 = 6%. At $833, that bond paying 5% is just as attractive as all of the new $1,000 bonds paying 6%. Yields go up when interest rates go up!

Greater yields are good for retirees, who generally need income-producing investments to fund their lifestyles. But it also reins in capital markets. Banks will be more inclined to hold their reserves as opposed to loaning them out. High-risk projects won’t get funded and neither will those with poor credit. Every time yields rise, the credit window closes just a little bit and liquidity gets sucked out of the system. This slows economic growth.

Multiples compress

The amount you’re willing to pay for taking the risk on a stock can be thought of as an “equity premium”. It’s essentially the difference between the company’s earnings and the risk-free rate of return mentioned earlier. As interest rates rise, the equity premium narrows. The company isn’t necessarily earning more, but the other half of the equation has been driven higher which eats into that premium. You’re probably not thrilled with this if you’re an investor.

For the company to keep that same equity premium, it will have to increase the amount it earns. For example, if the risk-free rate is 1% and the company is earning 6%/share, then your equity premium is 5%. If the risk-free rate rises to 2%, the company will have to earn 7%/share to maintain that same equity premium. But this isn’t automatic. Companies can’t turn on a money faucet and watch dollars pour out.

This means that the price of that company’s shares will have to come down to compensate. It’s the only way to maintain the equity premium. This phenomenon is known as multiple compression, and it poses serious headwinds for all stocks.

Speculation dries up

With equity prices dropping, speculation starts to dry up. Consumer sentiment takes a bearish tone. Investors that sought out equities because there was no other place to go will be tempted back into the safety of bonds as rates rise. This, too, reduces demand for stocks and drives down the prices even further.

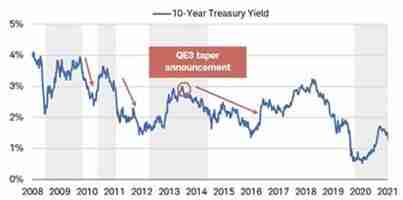

Mortgage rates rise, too

The most popular mortgage in America is a 30-year fixed mortgage. Rates for this are pegged to the US-10 year treasury. As bond yields rise, so too do mortgage rates.

Higher financing costs means a greater monthly payment. Almost overnight, the amount of house borrows can afford drops. This slows the rate of growth in house prices and in some cases turns them negative.

Pulling it all together

Interest rates are arguably the most powerful tool a central bank has to slow down an economy that is overheating. We can expect stock and bond prices to take a hit this year. Whether markets finish the year in positive territory will be a tug of war between how quickly the Fed hikes rates and how much companies can realistically earn. Housing prices will/should finally start to slow, savings accounts might actually be tempting by the end of the year, and the brake-neck pace of economic expansion we saw over the last two years will begin to temper.

This is the medicine needed to tame inflation, and its bitter. Buckle up!