Roth IRAs are wonderful tools to help you save and prepare for retirement. But only people whose income falls below certain thresholds can contribute directly, which makes accessing this vehicle difficult for higher income earners. There are workarounds available through after-tax Roth conversions from pre-tax retirement accounts, commonly called “backdoor” Roth IRAs, but the rules governing these can be cumbersome and it’s easy to make mistakes. In this article, we’ll show you the basics of how these accounts work, how to contribute, and how to make the most of them even when you can’t fund them directly.

The Basics

Roth accounts come in two flavors: Roth 401(k)s and Roth IRAs. Each type of Roth is funded with after-tax dollars, grows tax-free, and offers tax-free qualified distributions as well. A 10% early distribution penalty is assessed on all distributions that take place prior to age 59.5, though Roth IRAs offer a special exception in which you’re allowed to withdraw your contributions, not earnings, prior to that age without penalty.

Moreover, neither Roth 401(k)s nor Roth IRAs are subject to mandatory Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) at age 73 (or age 75 depending on your birthday). This means that money can grow and compound tax free for decades before rolling the funds down to the next generation or spending them yourself.

Arguably the biggest distinction in these accounts, and the crux of this article, is in how these accounts are funded. Anyone can contribute to a Roth 401(k). There are no restrictions based on age, income, assets, or anything else. You can contribute so long as your employer sponsored retirement plan offers a Roth option, and you can contribute up to the 402(g) elective deferral limit, which is $22,500 in 2023 or $30,000 with a catch-up contribution if over age 50. But Roth IRAs are different. Only taxpayers with income below certain levels are allowed to contribute. (Note, income is earned income and is determined from your Modified Adjusted Gross Income MAGI). Those with higher incomes are completely phased out as income increases. The maximum contribution for a Roth IRA is just $6,500 (or $7,500 if over age 50).

After Tax Roth Conversions via a “Backdoor”

Contributions to Roth IRAs have many restrictions, but conversions to a Roth IRA have zero restrictions! Anyone can convert but only some can contribute. This is where a workaround can be used to make an after-tax Roth conversion from a pre-tax IRA.

Unlike a Roth IRA, anyone can contribute to a pre-tax IRA. The only rule for is that you must have earned income that is at least as much if not more than what you contribute. The limits that apply to Traditional IRAs are on who can deduct their contribution. To be explicit before we move on – Traditional IRAs can hold both pre-tax and after-tax money! The same is true for 401(k)s. It is only in Roth accounts where mixing tax types isn’t allowed. Roth accounts will only ever hold after-tax money.

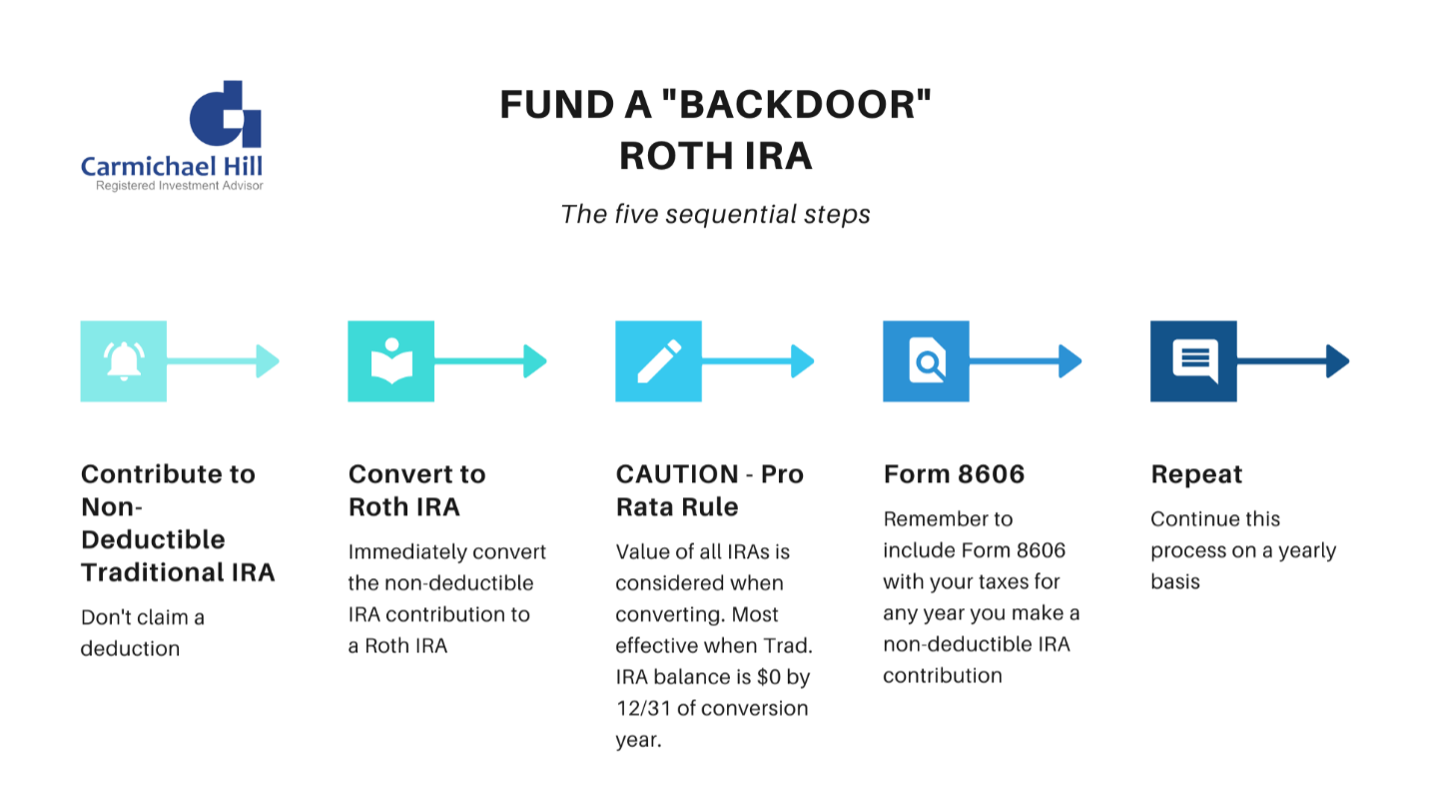

At the highest level, a “backdoor” Roth IRA works by making a non-deductible (i.e. after-tax) contribution to a traditional pre-tax IRA followed by an immediate conversion of that amount to a Roth IRA. Since you don’t deduct the contribution made to the traditional IRA, and since the conversion is done immediately after without allowing any time for growth in that IRA, the conversion will not generate any additional tax. The intent is to make this look and feel just like a Roth contribution but with a few extra steps along the way.

For those with a legal background, court rulings and IRS guidance have established that this process is not a violation of the step transaction doctrine. Despite the name, after tax Roth conversions via a “backdoor” are an entirely kosher and well established retirement planning method.

Spouses can do this, too!

After-tax Roth conversions are typically done from your own individual earnings, but it’s not a necessity. A spousal IRA contribution can also be made from a working spouse on behalf of a non-working spouse as well. This means that the “backdoor” Roth can be done on behalf of a stay-at-home parent or even or a spouse that may have retired a few years before the other! The only rule is that earned income must be at least as much if not more than the total IRA contributions.

Don’t forget your tax forms

Let’s dig into the details of this a bit more. You’ll need to make certain disclosures and reports to the IRS when you complete this transaction. You will receive a 1099R each year that you do a backdoor after-tax Roth conversion. A 1099R is generated every time money leaves a retirement account, which in this case is the after-tax money leaving your traditional IRA for your Roth IRA.

Box 2a on form 1099R, which states the taxable amount of the distribution, is likely to state the full value of the distribution. The financial institution that generated that 1099R doesn’t know your tax situation and doesn’t know that you didn’t take a deduction for the money you shoved into the traditional pre-tax IRA. It’s up to you to correctly report to the IRS, and that’s why you will need to file form 8606.

This form is used to report non-deductible contributions made to a traditional IRA. You are required to track the basis in your Traditional IRA. Your custodian will not do it for you! You must file form 8606 for every year you make a non-deductible IRA contribution. Without this the 1099R will tell an inaccurate story that could cost you extra in taxes.

Here’s a final wrinkle in all this: most high-income earners are precluded from making deductible contributions to a Traditional IRA, but not all. The rules around who can deduct vary based on income, tax filing status, and the availability of a workplace retirement plan. If you are in the rare category of being able to make a deductible IRA contribution, then form 8606 isn’t needed. Follow the steps above to make a pre-tax contribution followed by an immediate taxable conversion. It’s still the same tax-wise as if you contributed after-tax money to a Roth IRA.

The Pro-Rata Rule

The process for completing an after-tax Roth conversion is itself rather perfunctory and straightforward so long as you file the correct tax forms. But there are two little known rules that can come into play and make a mess of your tidy Roth conversion transaction. The first of these rules is known as the Pro-Rata rule.

This rule says that any amounts converted from a pre-tax account to an after-tax Roth account are done so pro-rata between pre-tax funds and after-tax funds. It’s a mouthful, but the key takeaway is that if you have any pre-tax funds in your IRA at the time you make and subsequently convert your after-tax contribution, then a portion of that conversion will be taxable. It’s easiest to see with an example:

The pro-rata rule in action

Jill Thompson has $15,000 of pre-tax funds in her IRA. She makes a $5,000 non-deductible contribution, which takes the total value of her IRA to $20,000. She goes ahead and converts that $5,000 non-deductible contribution as part of an after-tax Roth conversion via the ‘backdoor’ we’ve talked so much about. Jill is going to owe tax on this transaction.

Remember, $5,000 of the total $20,000 is in after-tax funds, which is 25% of the account. Because of the pro-rata rule, only 25% of the conversion can be from after-tax funds! Jill is not allowed to isolate just the $5,000 of after-tax funds in her Roth IRA. This means that $5,000 x 25% = $1,250 will be non-taxable to Jill while the remaining $3,750 will be taxable.

Jill gets no deduction for the $5,000 contribution and still gets hit with another $3,750 of taxable income on top of it! Double whammy.

If you’re thinking at this point, “why not just open a new IRA for the non-deductible contribution”, then congrats! You’re on the right track. This is exactly what smart planners did in the early days to circumvent this rule. It coincidentally led to the creation of the second rule – the IRA aggregation rule.

The IRA Aggregation Rule

The IRS responded quickly to planners finding an easy workaround to the pro-rata rule. The fix was the implementation of the Aggregation Rule, which says that you can’t isolate IRA accounts when completing conversions. All IRAs are added up and aggregated together when determining the pre-tax and after-tax amounts for conversions. Let’s expand on the example above to see how this works.

The aggregation rule in action

Frustrated with the pro-rata rule, Jill decides to keep her $15,000 pre-tax IRA and open an entirely new IRA for her $5,000 after-tax contribution. She decides to convert only the account with the after-tax contribution, thinking incorrectly that the pro-rata rule won’t apply since the only money in that account is after-tax money! However, Jill is subject to the aggregation rule as well as the pro-rata rule. The IRS won’t let you isolate after-tax money within an account, nor will they let you isolate which account you convert. For tax purposes, the IRS adds up all IRA accounts as if they were consolidated into one big IRA and then applies the pro-rata rule. Splitting accounts makes no difference. If you have any pre-tax money in your IRA when you make and subsequently convert your after-tax contribution, then that pre-tax money is going to impact your conversion!

A so-so workaround for the Pro-Rata and Aggregation rules

Critically (thankfully?), 401(k)s and other workplace retirement plans are not included in the aggregation rule. That rule only applies to IRAs. A simple and effective workaround is to roll your pre-tax IRA balances into your 401(k). And yes, you can isolate just the pre-tax amounts when you do this. 401k plans can only accept pre-tax balances from pre-tax accounts. Even if you wanted to, you cannot roll your after-tax IRA contributions into your 401k. In Jill’s case, she’ll need to roll $15,000 to her 401k and leave it at that. With just $5,000 left in any IRA, all of which is now after-tax, she can complete her after-tax Roth conversion without issue.

This does come with some drawbacks. 401(k) plans often have limited investment options, and you may not have access to the securities and investment vehicles you prefer, such as individual stocks. Moreover, 401k plans often have administrative expenses that are paid by the plan participants. This is an increased cost that isn’t shared in IRAs. In large 401k plans this cost is often miniscule, but it can be a tangible factor in smaller plans.

Be aware of the 5-year rules

After-tax Roth conversions via a “backdoor” are a long-term planning strategy. Roth IRAs work best when you let the money you have in them grow and compound tax free for as long as possible. This is not typically a planning strategy you would use if your end goal is to simply spend down the Roth account within the first few years of making those after-tax contributions. The tax-free growth you would earn on a maximum contribution of $6,500/year ($7,500 if over age 50) is likely to be negligible and arguably not worth the rigmarole of completing this multi-step transaction in the first place!

But if you do, there are two separate 5-year rules to be aware of. The first is related penalties on converted amounts. If you are under age 59.5, then you must wait a full five tax-years before you can withdraw your converted principal penalty free. (This penalty disappears at age 59.5, so it could be shorter if you convert and hit age 59.5 within that five-year period). The intent of this rule is to keep people from completing Roth IRA conversion and immediately withdrawing the money to skirt the early distribution penalty from a pre-tax retirement account, as distributions of principal from a Roth account can typically be withdrawn tax and penalty free any time before age 59.5.

The second five-year rule applies to taxes on earnings in the Roth IRA. Regardless of your age, you must have had a Roth IRA open for at least five tax-years to receive the benefits of tax-free growth. It doesn’t matter if you had an account open for five years, then closed it down, then opened a new account ten years later. Gaps are fine. Satisfy this rule once and it stays satisfied for life.

Ideally, these rules won’t come up and won’t impact you. You’re a long-term investor looking to optimize the tax-efficiency of your investments and are completing after-tax Roth conversions with the intent of letting your Roth grow for many years. Consider a taxable account for savings if you don’t have time on your side and expect to be withdrawing funds in short order.

The mega ‘backdoor’ Roth 401(k)

The ‘backdoor’ Roth IRA concept can also be done in a 401(k), but with some slight differences. First and foremost, your 401(k) must allow for pre-tax money, Roth money, and non-Roth after-tax money. Whether it does is determined by your company, and if they haven’t designed your plan to allow for each of those classes of funds then this strategy won’t work.

Let’s assume that you have each of these different types of funds available to you. You can contribute up to $66,000 to your 401(k) in 2023. This is made up of your contributions, which are as much as $22,500/$30,000 depending on whether you are under/over age 50, any employer contributions made to your account, and the rest up to $66,000 which takes the form of non-Roth after-tax contributions.

Those non-Roth after-tax contributions can be converted to a Roth 401k. This means that you can effectively get up to $66,000 in a Roth-type account in any given year, less whatever your employer puts in. The difference between Roth money and non-Roth after tax money is that the former grows completely tax free while the latter grows tax deferred.

Pro-rata and Aggregation rules in 401k plans

The pro-rata rule applies to 401ks, which is a bummer. If you make pre-tax contributions as well as non-Roth after-tax contributions, then a portion of your conversion is going to be taxable. You can’t simply isolate those non-Roth after-tax contributions. But the aggregation rule doesn’t apply to 401k plans! This means that the pro-rata rule is likely to be far less painful when applied to your 401k than it would be when applied to all of your IRAs.

Fantastic options for the self-employed

If you have self-employment income from a side-hustle or your full-time job, then you have some added flexibility. You can establish a 401(k) plan in which you make only ‘employee’ salary deferrals up to $22,500/$30,000 as well as employer match money or profit sharing contributions. (Remember, you are both employer and employee for purposes of your 401k plan when self-employed). A second 401(k) plan can be established and funded with only non-Roth after-tax contributions that are subsequently converted to Roth 401k, or simply rolled out and converted directly to a Roth IRA. This strategy works well since the aggregation rules don’t apply to 401k plans. You can effectively isolate your after-tax contributions for conversions.

Note though that the $22,500/$30,000 402(g) limit is aggregated across all 401k plans. If you have a job in which you collect W2 income as well as another job in which you receive a K-1 or file a Schedule C with your taxes, then you can simply hit the 402(g) limit on the plan with your W2 income and create one additional 401k plan under your business that is used solely for the non-Roth after-tax contributions.

Tying it all together

After-tax Roth conversions via a “backdoor” is a tried and true tax management strategy for high-income earners, but you need to know the rules. These are nuanced transactions with many moving parts. Even when you do get all the rules right, your conversion strategy may still impact which tax credits you qualify for and which deductions you can take, which tax bracket you fall into, whether you’ll be forced to pay Medicare surcharges, and that’s to say nothing of how it may impact your state income taxes.

We wrote the full and unabridged primer on all things Roth conversions, and it’s a beast. When you’re ready for a few pointers on how to do this correctly yourself, or if you want someone to take the lead and ensure this is done correctly on your behalf, give us a call. We’re ready to help.